Copy from Randall Lloyd

Father: Henry BEAVER

Mother: Lurana Elizabeth COCKRILL

Family 1 : Jennie ARMSTRONG

_Conrad BEAVER ______+

_David BEAVER ____________|

| |_Mary Jane KNEISSLY _

_Henry BEAVER ______________|

| | _John STRICKLER _____+

| |_Anne STRICKLER __________|

| |_Barbara BRUMBACK ___+

|

|--Oscar Anderson BEAVER

|

| _William COCKRILL _+

| _Anderson COCKRILL _|

| | |_Frances JONES ____

|_Lurana Elizabeth COCKRILL _|

| _Joseph VENABLE ___

|_Rebecca VENABLE ___|

|_Lucy DAVENPORT ___

Notes:

Copy from Randall Lloyd

|

Oscar Beaver is listed in the 1880 Census for Township #6, Lemoore, Tulare County, as a 24 year old saloon keeper born in California (father in Pennsylvania [sic] and mother in Kentucky). Also listed as a border in the household was a Charly G. Lamberson. Oscar was also a homesteader and farmer, and according to family tradition, gained ownership to land next to his father's in Lemoore by planting an orchard on it. The orchard does show up on the county plat maps indicating Oscar's ownership. In the Federal Land Patent Deed Index for Fresno County, an Oscar A. Beaver is listed as recording Patent #4306 for homesteaded land at Township 13 South Range, Number 28 East, Section 25 on 22 Mar 1889. When organized in 1852, Tulare County included Fresno, Kings, and Kern counties, plus other territory. Fresno County was organized in 1856 and Kern County in 1893 -- the boundaries between these various counties were shifted around several times between the 1850's to around 1910.

|

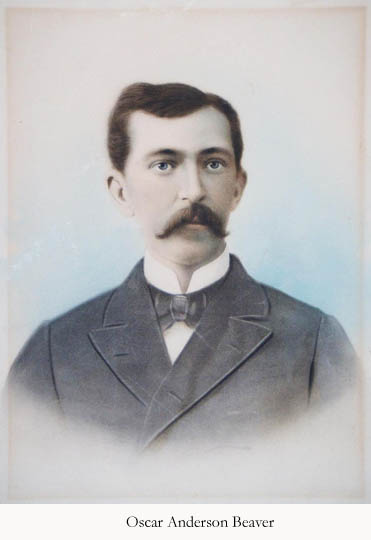

Photo from Ross Williams

|

The most important thing about Oscar Beaver it appears, was his death. As a part-time Deputy Sheriff for the little town of Lemoore, which was at that time in Tulare County, California, Oscar had the misfortune of being shot to death in the line of duty, by two suspected train robbers, Christopher Evans and John Sontag. His murder at the age of 35 was at the forefront of a series of events which defined the histories of these two infamous California outlaws. It is a 19th century story of the Old West so wrapped up in the politics, economics, and social conventions of this time, that it is difficult to unravel without the whole bundle sprawling open, and spilling out way beyond the object of this particular genealogy. Yet, it is also an intriguing story that is still resonate with the sensibilities and values of our present time. Twelve years before the hapless Oscar met his end in Chris Evan's barn in Visalia, a group of settlers and local law enforcement officials attempting to serve eviction papers for the Southern Pacific Railroad, squared off and when the dust settled, six were dead. This incident, which became known as the Mussel Slough Tragedy, was the most prominent of many skirmishes for several years between the railroad and the settlers of this area. That other Cockrill family members, besides the Beavers may have also had some involvement in other Tulare and Fresno county conflicts of these times (1880-1890's) is a subject for continued research. |

|

In an "exclusive" interview published in the October 7, 1892 issue of The Examiner, Chris Evans had somewhat less regretful things to say about Oscar Beaver: |

|

"As to the killing we have done, it seems to me it has been a pretty good riddance for the county of the so-called `bad man.' Take Oscar Beaver. He killed `Sheepman Kripe' near Lemoore in cold blood, and another time he shot a fellow in the Laurel Palace saloon in San Francisco."

|

|

In perhaps the most carefull study of the Evans and Sontag story to date, Train Robbers & Tragedies: The Complete Story of Chris Evans, California Outlaw (Visalia, CA: Tulare County Historical Society, 2003), author Harold L. Edwards, goes into some detail (p. 46) about this killing of the colloquially-named Sheepman Kripe by Oscar Beaver on May 19, 1888. Upon the land which Oscar was homsteading (mentioned above), a sheep rancher by the name of J. N. Cripe, had constructed a well for water, sometime before Oscar had moved into the area. Weeks after he established his homestead, a fight occurred between the two men over this well and its equipment, and Cripe was fatally shot by Beaver in self-defense. After two trials, Beaver was convicted of manslaughter, but because of his "excellent character," the judge sentenced him to the minimum of one year in the state prison. Public support for Oscar in this incident ran high in the community, and a petition for pardon signed by "the sentencing judge, the prosecutor, the defense attorney, local state legislators, local peace officers, and numerous prominent citizens," was sent to the governor of California. As a result, Oscar Beaver was pardoned from serving the sentence of his manslaughter conviction on January 10, 1890. That Oscar may have been involved in another shooting, appears to probably have been a fabrication of the San Francisco Examiner at the time.

|

|

Another book published about Evans and Sontag is Evans & Sontag: The Famous Outlaws of California, by Hu Maxwell (Fresno, CA: Fresno City and County Historical Society, 1981). This work was originally published in 1893, and the author was a reporter and newspaper editor who had covered the story when it occurred for the Fresno Evening Expositor and the San Francisco Chronicle. Maxwell also takes a far more unfavorable review of the exploits of the outlaws than Smith's version of the story. In the 1981 reprint (the paperback of which is still obtainable from the Fresno City and County Historical Society), many of the newspaper illustrations of that time are included as well as additional supporting material compiled and updated by Charles W. Clough.

Yet another piece of "first-hand" writing about Evans & Sontag, is the recollection which John Sontag's brother published, titled A Pardoned Lifer: Life of George Sontag Former Member Notorious Evans--Sontag Gang Train Robbers, by Opie L. Warner (San Bernardino, CA: The Index Press & George C. Contant, 1909), in which George Sontag (who also went by the name George Contant), as an "eyewitness," substantially supports the railroad and local law enforcement claims of the duo's involvement in the series of train robberies which led up to their initial confrontation with the law. Contant also essentially blamed Evans for corrupting his brother. He had been the major witnesses against Evans at his trial and in turn, was particularly despised by Evans and his family after that time. Exploiting his own past even further, Contant, whose prison sentence was commuted in 1908, formed a film company in 1914, and made an autobiographical movie in which he also the lead actor. The Folly of a Life of Crime was also apparently the first film ever made in Chico, Butte County, California (a later location site for filming more well-known films, such as The Adventures of Robin Hood [1938], Gone With The Wind [1939], and Red Badge of Courage [1951]). Sadly, it appears that a copy of The Folly of a Life of Crime no longer exists.

Chris Evans also wrote a book while he was in prison, titled Eurasia, and it was an odd, little utopian text. It contained Evan's political views about society, government, business, and ironically a somewhat brutal view about how punishment should be meted out for crime.

Another well-informed contemporary scholar of the Evans and Sontag story has been William B. Secrest. He has written about the duo in various publication including a chapter about them in California Desperadoes: Stories of Early California Outlaws in Their Own Words (Clovis, CA: Quill Driver Books/ Word Dancer Press, Inc., 2000). This particular chapter also contains several images and numerous, well-researched details about Evans and Sontag. Two other significant books important to the Evans and Sontag story are Robbers of the Rails: The Sontag Boys of Minnesota, by John J Koblas (St Cloud, Minnesota: North Star Press, 2003), and Dalton Gang Days: From California to Coffeeville, by Frank F. Latta (Exeter, CA: Bear State Books, 2001).

The Tulare County Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin, Los Tulares, has had some interesting articles about Evans and Sontag as well. Most notable, are two articles by Leland Edwards, "Chris Evans' Early Troubles," (Number 204, June 1999, details Evans hot temper and early run-ins with the law), and "Molly and the Kids," (Number 218, September 2002, details Evans relationship with his family).

In the May 1995 (Volume 26, number 2) issue of the Smithsonian (pages 84-94), there is another retelling of the Evans and Sontag story, this time putting it in the context of the Mussel Slough Tragedy, in "Chris Evans could always be relied on to pull a fast one," by Stephen Fox (with contemporary illustrations by Toni Kurrasch). The author goes into some detail about how the Southern Pacific Railroad suppressed much of the publicity about the duo's exploits by providing free passes and large annual "advertising" payments to the newspapers in the area. This worked to a certain extent except with William Randolph Hearst who had a personal dislike against "The Big Four." He took their advertising money for awhile (which was to be $30,000 over 30 months) but then did a number of front-page "exclusives" which both sold a lot of newspapers and embarrassed Southern Pacific enough to suspend payments and accuse Hearst of being not judicious and a Bohemian.

A series of articles, "A California Story: Evans and Sontag, and Uncle Oscar," published in 1992, in the June, July, and August issues of the Visalia Valley Voice by Charles Huddleston, gives a Beaver Family view of the story. However, as often is the case when such crimes were committed, one usually finds more to say about the perpetrators than the victim. Considering that the author was the grandson of Francis Marion Beaver, one of Oscar's brothers, the details of Oscar's life (as a defense to what Evans had said about him, if anything else) and murder are overshadowed by yet another retelling of the adventures of Evans and Sontag. From a family history viewpoint, I wished for a more complete telling of Oscar's short life, what he did besides being a part-time deputy, and what happened to his family. I was hoping at least, there would have been a picture of Oscar in the series of articles. I had seen a photograph of Oscar's grave site covered with flowers at the time of his burial but it appeared to me that a photograph of Oscar Beaver himself was not in existence. It was a common question that I asked for many years, of Beaver family members and Evans and Sontag researchers which I had come in contact with, but nothing was known. What one would see of him in the various articles and books that were subsequently published, was this engraving from the newspapers done at the time of his killing: |

|

Recently however, Randall Lloyd emailed me a copy of the wonderful image which is at the top of this page. From Mr. Lloyd's 28Feb2008 email: |

|

... I recently came across your Cockrill family web site while searching for information about my family. I was specifically searching for Oscar Beaver, expecting that there might be something about his life and death. In reading your description of the events, I note that you mention there are no extant images of him. I have what appears to be a water color of Uncle Oscar that is very similar in form to the black and white drawing on your page, although more complete. The picture was given to me by my uncle, Charles Huddleston, in the 1970s along with a draft manuscript on the Sontag and Evans affair. The picture was framed and has seen some wear. There is no date anywhere to be found with it, and I do not know how my uncle -- now deceased -- obtained it.

|

|

Email from 3Mar2008: |

|

I have taken a closer look at the portrait and see that it probably is not a water color. It might be a pastel, or perhaps even a print of some sort. Whether this is the source of the newspaper etching or that came from an earlier picture, it seems likely that this likeness is the source of the newspaper etching. My surmise is that it was a wedding pose, given the coat, collar, and tie, and thus probably reflects Oscar around the time of his marriage -- about 1884. The custom for the time seems to have been to take a photograph, which might mean that this is a reproduction of that photo. However, the color of hair and eyes would need to be related by someone familiar with them, since any photo would have been black and white. The hair and eye color seem to be correct, at least so far as Oscar's son, John Crawford Beaver, had the same hair and eye characteristics. I have thought about where my uncle would have obtained this picture and still can't come to any conclusions. My uncle kept it in the closet of his home office in Visalia. My grandmother, Myra Beaver Huddleston, was still living when I was given the picture. So, he probably didn't get it from his mother. I would expect an original picture to have been held by John Crawford Beaver. I have no indication that my uncle was close to John C, and further, from the records, it appears that Jennie Armstrong Beaver and John C Beaver lived lives apart from the Beavers and, therefore, the Huddlestons.

|

|

|

|

There are several items about Evans and Sontag on the web. A good place to start is Ron Affolter's web page, SONTAG BROTHERS: "Southern Minnesota's Own Train Robbers," which contains information about the Sontag family as well as links to other Evans and Sontag sites on the web.

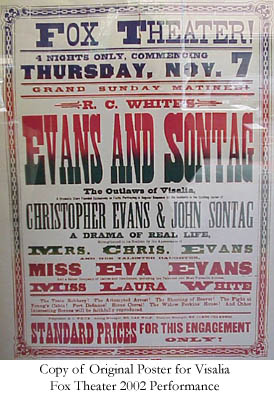

Also long thought to have been completely lost, the more or less biographical play written by R. C. White, "Evans & Sontag: The Visalia Bandits” which had been written at the time of Chris Evans' trial to aid in supporting his family and obtaining funds for his defense, has been recently found. A descendant of the author found a handwritten copy of the play (with the working title of "Wiley Smooth in Evans & Sontag" written on the cover), along with complete stage directions and music score in an old family trunk (an account of this discovery can be found the May 25, 2002 issue of the Visalia Times Delta). The discovery came at a fortuitous time, in celebration of the City of Visalia's Sesquicentennial, the Tulare County Historical Society, and with Jay O'Connell as the producer, put on a full performance of the six act, "blood and thunder" melodrama in the old, but recently refurbished Fox Theater in downtown Visalia in November of 2002 (see announcement). The performance was an authentic reproduction of 19th century style of stage craft as possible: complete with rotating interior/exterior house shell, hand painted background scenes on rolls of canvas for quick set changes, guns which fired with loud sparking retorts, and even a live horse on stage. Also, an extra added touch were "protesters" in period clothing outside the theater with signs condemning the play's immorality (as well as Oscar's "widow" in 19th century, black mourning clothes, carrying a sign that read "Chris Evans done killed my man!"). Indeed the play had been banned from Visalia during its original outing. However, having the opportunity to see such a 19th century piece of popular entertainment put on in its entirety in 21st century Visalia was indeed a rare treat. Though the producers of play remained true to their source and realized the play superbly, the play's content veered from the historical truth rather significantly. Certainly the play's intention was to present the duo's innocence in the best light possible. Though one would expect heroic and rousing speeches about individual rights within a ham-fisted, 19th century melodramatic context, I was somewhat surprised that the issue of the Southern Pacific Railroad was transformed in the play into the representation of the villainous railroad detective, Wiley Smooth. A broadly satirical and no doubt libelous characterization (particularly if it had been presented in our litigious times) of real-life Southern Pacific Railroad Company Detective Will Smith, who indeed had a "less than admirable" public image, according to Harold L. Edwards' account, and roundly hated by Evans, and who was particularly despised by him as a "blood sucker!". In the play, the moustache-twisting Smooth, effectively frames Evans & Sontag for the Collis train robbery, in order to end Evan's daughter Eva's relationship with Sontag, so that he might have her all to his own, black-hearted, evil self. That the subject of the "Big Four" and their strangling monopoly over the subsistence living, family-own farm as a justification for the violence, was hardly ever alluded to in the play. After all, this was not Chekhov I suppose, and 19th century audiences for popular forms of entertainment, needed something a bit more venial than an erudite analysis of Southern Pacific's evil twisting of short and long haul rate schedules. But one also wonders if out-spoken criticism against the railroad monopoly, was not much more louder and articulate several years later with such things as the publishing of The Octopus by Frank Norris, and the campaign for governor by Hiram Johnson.

|

|

|

|

Mr. O'Connell has since written a book about Eva Evans, Train Robber's Daughter, the Melodramatic Life of Eva Evans, 1876 - 1970) (Northridge, CA: Raven River Press, 2008) which has garnered several good reviews.

Certainly, much more could be detailed here on the Evans & Sontag story which would go way beyond the scope of this page (as absurd as its length already is) and forgetting that the killing of poor old Oscar Beaver was at the forefront of duo's story. In this regard therefore, I have provided a condensed and general history of the outlaw pair, which can be accessed from this link.

Much more detail about this story can also be found in the newspapers of the times as these events unfolded. The Evans & Sontag story was one of the first wide-spread, spectator events, where an emergent popular media took full advantage of an increased post-Civil War literacy of the American public, to present "news" as a form of popular entertainment. The following are some of these newspaper articles about the outlaw pair and the death of Oscar Beaver. A side note: there is a place name in

these newspaper articles which is now politically incorrect and just

plain offensive, though not an uncommon term for the times which these articles

were written (and as a Beaver family descendant has pointed out to me, this

area of California was settled by many ex-Southerners after the Civil War).

While one may not be able to adequately apologize for such language with its

evil history, we intend to remain sensitive about differences between the two

eras, and the use of such terms that are now a source of continued

discomfort.

|

|

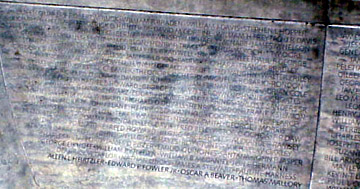

Oscar Beaver's name can be found on the first wall of law enforcement officers who died in the line of duty at the Law Enforcement Memorial in Washington D. C. I had walked by this monument on previous visits to the area without realizing it was there. |

|

|

|

|

|

Many thanks to Nita Van Cleave, a descendant of Chris Evans' fraternal twin brother, Tom Evans, for pointing me towards several of the sources used here as well as providing help with continued researches. As distantly as we might be related to Chris Evans and Oscar Beaver, there is something ironically appropriate to this contemporary collaboration.

|

![]()

This page created on 02/05/01 16:08. Updated 03/15/08 17:30.